Nikolai Gogol: The Satirical Architect of Russian Literature

Honoring the Satirists and Thinkers Who Altered Our Perspectives #67

Voice-over provided by Amazon Polly

Also, check out Eleven Labs, which we use for all our fiction.

Preface

Nikolai Gogol (1809–1852) remains one of the most enigmatic and influential figures in Russian literature. Born in Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire, he crafted works that laid the foundation for the development of Russian realism while employing biting satire to expose the absurdities of bureaucracy, social hierarchy, and human folly. His major works, including The Government Inspector and Dead Souls, hold a mirror to the hypocrisy and corruption of his time, creating a literary legacy that inspired generations of writers, including Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. This installment of Honoring the Satirists and Thinkers Who Altered Our Perspectives examines the life, works, and enduring significance of Gogol’s satire.

Early Life and Influences

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol was born on March 31, 1809, in the Ukrainian village of Sorochyntsi, part of the Russian Empire. His family belonged to the minor gentry, and his father, Vasily Gogol-Yanovsky, was an amateur playwright who introduced young Nikolai to the world of literature and theater. His mother, Maria Ivanovna, was deeply religious and played a significant role in shaping his moral and philosophical outlook. His Ukrainian heritage played a significant role in shaping his literary imagination, particularly its folk traditions, superstitions, and humor, which later permeated his works. The oral storytelling traditions of Ukraine, filled with grotesque humor and ghostly legends, heavily influenced his writing style.

As a boy, Gogol was introverted and highly self-conscious about his appearance, leading to a sense of alienation that would later inform many of his characters. He displayed an early fascination with the eccentric and absurd, traits that would define his literary output. His schooling at the Nizhyn Gymnasium of Higher Sciences was both formative and challenging. While he excelled in creative writing and theater, he was often ridiculed by his peers for his awkward demeanor and nasal voice. His early writings were heavily influenced by Romanticism, and he experimented with poetry and historical fiction before fully embracing satire.

In 1828, he moved to St. Petersburg with dreams of becoming a celebrated writer and civil servant. However, his initial years were marked by hardship. Unable to secure stable employment, he briefly tried acting and even considered becoming a historian. In 1829, he self-published a sentimental poem, Hans Küchelgarten, which was met with harsh criticism, leading him to buy and destroy all available copies. This failure redirected his focus toward prose, where he found his true voice. His subsequent work, Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka (1831–1832), was a breakthrough—drawing heavily from Ukrainian folklore, it established him as a promising literary figure and earned him the mentorship of Alexander Pushkin. This period of literary exploration, coupled with his later experiences working various government jobs, deeply informed his satirical perspective on Russian bureaucracy.

Major Works and Themes

The Government Inspector (1836)

One of Gogol’s most famous plays, The Government Inspector, is a masterful satire of bureaucratic incompetence and corruption. The plot revolves around a small town’s officials mistakenly identifying a young, opportunistic traveler, Khlestakov, as an incognito government inspector. In their desperate attempts to bribe and flatter him, they expose their own venality, incompetence, and paranoia. The play's humor arises from misunderstandings, exaggerated character flaws, and an incisive critique of the Russian bureaucratic system, which Gogol saw as rife with corruption and self-serving officials.

The play was an immediate success, endorsed even by Tsar Nicholas I, who saw it as a critique of bureaucratic excess rather than an indictment of autocracy. However, many officials took offense at its scathing portrayal, forcing Gogol to leave Russia shortly after its publication. Over the years, The Government Inspector has remained one of the most performed Russian plays, with adaptations appearing in theaters across the world. Its themes of political incompetence and greed remain universally relevant, ensuring its enduring popularity.

Dead Souls (1842)

Gogol’s Dead Souls is often considered his magnum opus. This novel follows Pavel Chichikov, a cunning and unscrupulous man who travels through provincial Russia buying up the names of deceased serfs (or “souls”) from landowners to use as collateral for a government loan. The absurdity of the plot serves as a vehicle for exposing the moral decay, greed, and inefficiency of Russian society.

The novel employs a picaresque structure, with Chichikov encountering a series of grotesque characters, each embodying different aspects of Russian provincial life—avarice, self-delusion, bureaucratic incompetence, and social pretension. Inspired by Dante’s Inferno, Dead Souls was intended to be a three-part epic depicting Chichikov’s moral transformation, but only the first part was completed. Gogol, in a fit of religious fervor, burned the unfinished second part shortly before his death.

Beyond its critique of Russian society, Dead Souls is also an exploration of identity and self-perception. Chichikov’s interactions with various landowners serve as a satirical reflection of human nature, where greed and self-interest overshadow morality. The novel’s dark humor, coupled with its philosophical undertones, has solidified its reputation as a cornerstone of Russian literature. Scholars continue to debate its deeper meanings, with some interpreting Chichikov as a tragic antihero representing the unfulfilled potential of the Russian soul.

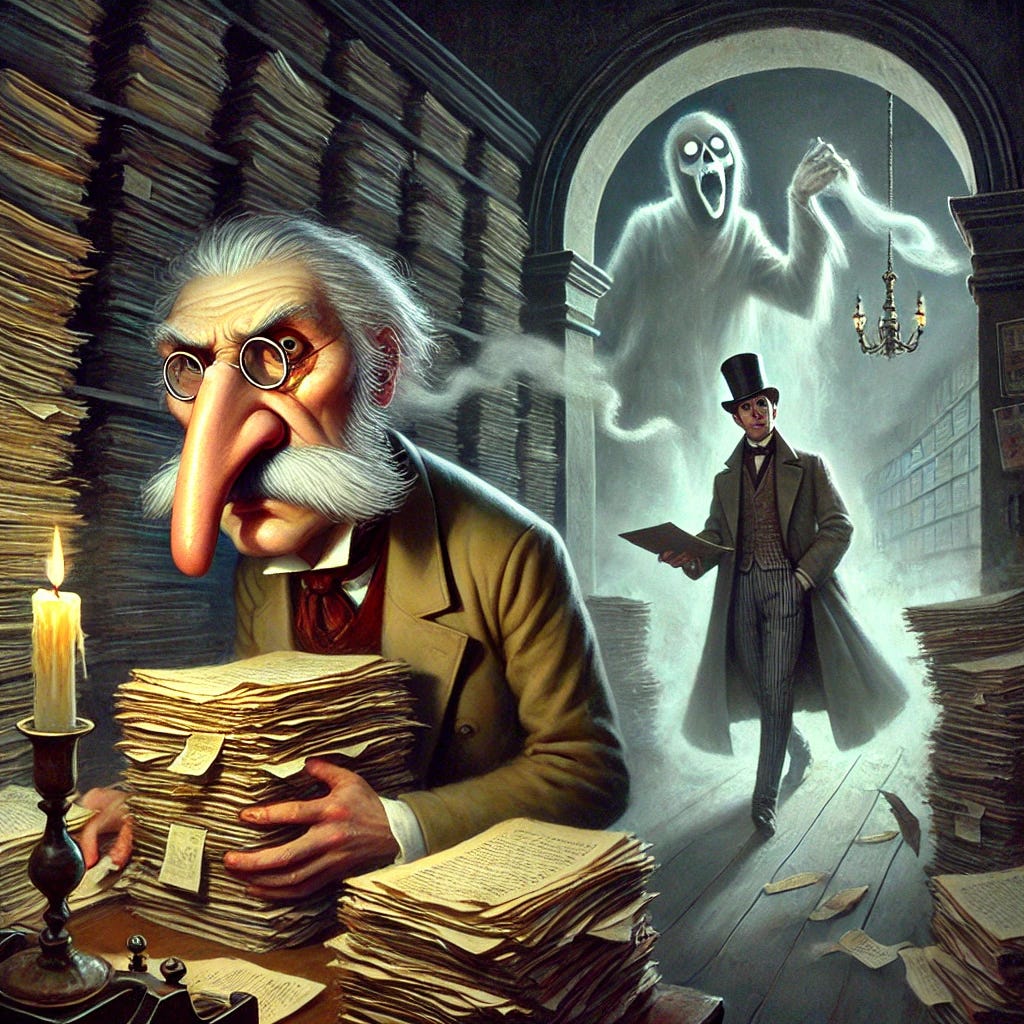

The Overcoat (1842)

Often regarded as a seminal work in Russian literature, The Overcoat tells the tragicomic story of Akaky Akakievich, a lowly government clerk who dedicates his life to copying documents. When his threadbare coat becomes unusable, he scrapes together money for a new one, only to have it stolen. His desperate attempts to seek justice are ignored, and he ultimately dies in misery, only to return as a ghost to haunt St. Petersburg.

This story is a profound meditation on bureaucratic cruelty and the dehumanization of the lower classes. Dostoevsky famously said, “We all came out of Gogol’s Overcoat,” underscoring its foundational influence on Russian literature’s concern with social injustice and individual suffering.

In addition to its social critique, The Overcoat is a deeply psychological work, capturing the alienation and insignificance of the individual within a vast, indifferent system. Akaky’s plight resonates with readers across generations, highlighting the timeless struggle of the powerless against unfeeling institutions. The story’s ghostly conclusion also foreshadows elements of magical realism, which would later influence authors worldwide. The Overcoat remains a frequently studied text, illustrating Gogol’s mastery of blending humor, horror, and human pathos in a singular narrative.

Rhetorical Style and Techniques

Gogol’s satire is distinguished by his surreal and grotesque humor, which often blends the absurd with the tragic. He pioneered a uniquely Russian blend of realism and fantasy, where mundane events spiral into bizarre, exaggerated spectacles that highlight the absurdity of human behavior. His narratives often feature a delicate balance between laughter and horror, making his critiques both entertaining and unsettling.

Irony and Hyperbole: The Government Inspector and Dead Souls are filled with exaggerated characters who reveal their flaws through self-delusion and grotesque behavior. His satirical style employs irony to expose the hypocrisy of bureaucrats, landlords, and government officials, exaggerating their traits to ridiculous extremes.

Symbolism and Allegory: The Overcoat serves as both a literal tale of poverty and a metaphor for social neglect and existential despair. Many of Gogol’s characters exist as embodiments of broader societal ailments, such as the hollow ambition of Chichikov in Dead Souls, who reflects the moral stagnation of the Russian gentry.

Unreliable Narration: Gogol often used ambiguous and misleading narrators, keeping readers uncertain about what to take at face value. His narrative style frequently employs digressions, sudden tonal shifts, and direct addresses to the reader, creating a sense of instability that mirrors the absurdity of his subject matter. This technique forces readers to actively engage with the text, questioning reality and the reliability of the storyteller.

Grotesque Realism: He had a unique ability to transform ordinary scenarios into nightmarish or exaggerated spectacles. His descriptions of people and places often border on the caricatured and monstrous, drawing attention to the deeper psychological and societal failings of his characters.

Dark Humor and Satirical Tragedy: Gogol’s humor is deeply intertwined with tragedy. His protagonists are often pitiable figures who become the butt of fate’s cruel joke, such as Akaky Akakievich in The Overcoat, who finds temporary joy in his new coat only to suffer an even greater downfall. His ability to make readers laugh while confronting them with deeply disturbing realities remains a hallmark of his literary genius.

Gogol’s use of these techniques set the stage for Russian realism while maintaining a dreamlike quality that would later influence absurdist and existentialist literature. His works remain a study in contradiction—hilarious yet bleak, structured yet chaotic, realistic yet fantastical—solidifying his place as one of literature’s greatest satirists.

Controversies and Criticisms

Gogol’s works were often misunderstood in his own time. While he aimed to provoke moral reflection, many saw his critiques as either too harsh or too ambiguous. His sharp satire of Russian bureaucracy and provincial life left many in positions of power uneasy, leading to both acclaim and controversy.

The Government Inspector angered bureaucrats and officials who recognized themselves in its satirical portraits. Many local and provincial officials feared the play's depiction of corruption would invite scrutiny of their own conduct, leading to whispers of censorship. Though Tsar Nicholas I reportedly enjoyed the play, its reception among the ruling class was mixed, with many seeing it as dangerously subversive.

Dead Souls was banned in some circles for its perceived cynicism and mockery of Russian society. While Gogol saw it as a moral critique meant to inspire self-reflection and change, some critics and readers took it as an unpatriotic condemnation of Russia itself. The novel’s ambiguous ending and grotesque characters left many unsettled, leading to accusations that Gogol had abandoned the ideals of Romanticism in favor of nihilistic despair.

In later years, Gogol’s religious views intensified, leading him to denounce some of his earlier works as immoral. Under the influence of an Orthodox priest, Father Matvey Konstantinovsky, he burned the second volume of Dead Souls, believing it to be spiritually harmful. During this period, he began advocating for a deeply religious life, urging his readers to reject materialism and embrace Christian humility. This shift alienated many of his literary admirers, who saw his renunciation of satire as a tragic loss to Russian literature.

Gogol’s final years were marked by self-imposed asceticism, fasting, and spiritual turmoil, culminating in his early death in 1852. His transformation from a biting satirist to a tormented religious seeker remains one of the most debated aspects of his legacy, illustrating the profound contradictions that defined his life and work.

Impact and Legacy

Gogol’s influence on Russian literature cannot be overstated. His works set the stage for Russian realism, influencing writers like Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Chekhov. His fusion of humor, social critique, and existential despair became a defining feature of Russian literary tradition. Dostoevsky, in particular, saw Gogol as a precursor to his exploration of psychological depth and moral struggle. Tolstoy, though more critical of Gogol’s grotesque exaggerations, acknowledged his unparalleled ability to depict the absurdity of social institutions. Chekhov, meanwhile, inherited Gogol’s blend of tragicomedy, crafting stories that reflect the same underlying sense of human frailty.

Outside of Russia, his legacy persists in global literature and theater. His grotesque characters and absurdist humor paved the way for modern satire, influencing figures as diverse as Franz Kafka, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Samuel Beckett. Kafka’s sense of bureaucratic absurdity in The Trial and The Castle echoes Gogol’s critique of Russian officialdom. Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita shares Gogol’s fascination with the supernatural as a means of exposing societal hypocrisy. Beckett’s theater of the absurd, particularly Waiting for Godot, reflects Gogol’s technique of blending humor with existential dread.

In modern Russia and Ukraine, Gogol remains a contested cultural figure—claimed by both nations, his works serve as a testament to the shared literary and historical legacies of the two cultures. Ukrainian scholars emphasize his deep connection to Ukrainian folklore, language, and storytelling traditions, while Russian critics highlight his contributions to Russian literature and his engagement with Russian societal issues. His explorations of corruption, alienation, and bureaucratic absurdity remain deeply relevant, resonating in contemporary political and social discourse. His works are frequently referenced in discussions on government inefficiency, social stagnation, and the individual’s struggle against oppressive systems. Even today, phrases from The Government Inspector are used to describe political scandals, and Dead Souls continues to be invoked as a metaphor for systemic decay and moral emptiness in governance and society.

Conclusion

Nikolai Gogol’s satire endures because of its uncanny ability to reveal both the ridiculousness and the tragedy of human nature. His works continue to challenge and inspire, offering timeless critiques of bureaucracy, social decay, and moral blindness. Whether through the tragic fate of Akaky Akakievich, the grotesque misadventures of Chichikov, or the chaotic deceptions of The Government Inspector, Gogol’s literary legacy remains an essential pillar of satirical literature, proving that humor and horror often go hand in hand when depicting society’s ills.

What makes Gogol’s satire particularly striking is its universality. While rooted in the specific sociopolitical realities of 19th-century Russia, his themes—corruption, alienation, the absurdity of power structures—transcend time and place. His exploration of bureaucracy’s dehumanizing effects speaks as much to contemporary institutions as it did to the imperial government of his day. The resonance of Dead Souls with modern discussions on greed and moral bankruptcy, or the way The Overcoat continues to serve as a stark warning against societal neglect, demonstrates the lasting relevance of his vision.

Furthermore, Gogol’s work remains a crucial bridge between the literary traditions of Romanticism and Realism, with elements of surrealism foreshadowing later modernist and absurdist literature. His influence extends far beyond Russia, shaping the storytelling techniques and thematic concerns of writers across the world.

Ultimately, Gogol’s satire is not merely an attack on society’s flaws but a deeply personal exploration of human frailty. His characters are not merely villains or fools; they are tragicomic figures whose struggles elicit both laughter and pity. This duality—wherein the grotesque becomes inseparable from the poignant—ensures that his work remains as vital and compelling today as it was in his own time.

Thank you for your time today. Until next time, stay gruntled.

Do you like what you read but aren’t yet ready or able to get a paid subscription? Then consider a one-time tip at:

https://www.venmo.com/u/TheCogitatingCeviche

Ko-fi.com/thecogitatingceviche

Conrad, I love this beautiful essay on Nicolai Gogol. I have long been a lover of Russian literature, despite its often gloomy and even cruel look at humanity. I recently read a collection of Gogol's short stories dealing with farmers and country folk. It was a realistic book, but more romantic in tone than most of his novels and stories. Thank you for getting me thinking of him; now I'll have to reread a Gogol book.